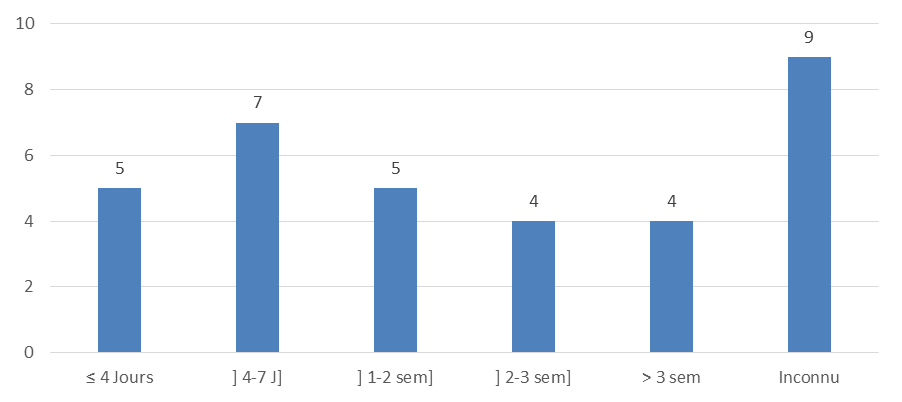

Consultation deadline

A period of 14.5 ± 9.9 J elapsed between the onset of symptoms and the admission of patients to our study. The review of the literature reports a similar delay, even sometimes greater than ours [18] [16] & [19]. However, there are works which reduce the time to 7-9 days shorter (Shomaker, K. L. et al., 2011; & Shomaker, K. L. et al., 2010) [20].

The relatively long delay is justified by the fact that many people resort to self-medication before consulting. Also, in many African countries, as in our study, many patients have difficult access to care, due to their geographical location, or the cost of examinations which is sometimes high. On the other hand, the short delay is seen in developed countries with more developed health systems, better access to care, better-off and more educated populations (from a health point of view).

Reasons for consultation and clinical signs

Fever, followed by cough, then dyspnea are the most recurring reasons for consultation. The same tripod of symptoms is found in many series [10], [21] & [22], without any particular order of succession. In other series [18], [9] & [23], chest pain takes precedence over dyspnea, but the other two symptoms remain predominant.

These differences are easily explained by simply observing the age of the study population.

We note that in populations made mostly or only children, the first tripod of symptoms is recurrent; whereas in an adult population, fever and cough are followed directly by chest pain.

Location of the effusion

The effusion is located on the right in the majority of cases (53.1%). Data from the literature for the last 10 or even 20 years (Koueta, F. et al., 2011; Goyal, V. et al., 2014; Dass, R. et al., 2011; Hicham, H. et al., 2018; & Subay, K. et al., 1991) [10], [24], [15], [25] & [19] show this right predominance.

The anatomy of the lower respiratory tract could justify such a distribution; the right main bronchus and lung being naturally larger than those on the left. This physiologically leads to a greater exposure to airborne germs, and therefore a greater risk of developing right pleuropneumonia.

RADIOLOGICAL DATA

The radiologic lesions were dominated by a "white lung" appearance, followed by radiologic alveolar syndrome and interstitial syndrome.

Many authors (Koueta, F. et al., 2011; LUKUNI MASSIKA, L. et al., 1990; Desrumaux, A. et al., 2007; & Brémont, F. et al., 1996) [10], [16], [21], & [26] report the same results in varying proportions, with a predominance of either a "white lung" appearance or reticulo-interstitial lesions.

This variability would be the subject of further study, but could be explained by the nature of the germs encountered in these studies, taking prior antibiotics can modify the behavior of the germs, as well as the formation of lesions. Also, it should be added that age would be an additional factor: the total opacities of a hemi thorax would tend to appear much more in children, in particular infants.

BIOLOGICAL ASPECTS

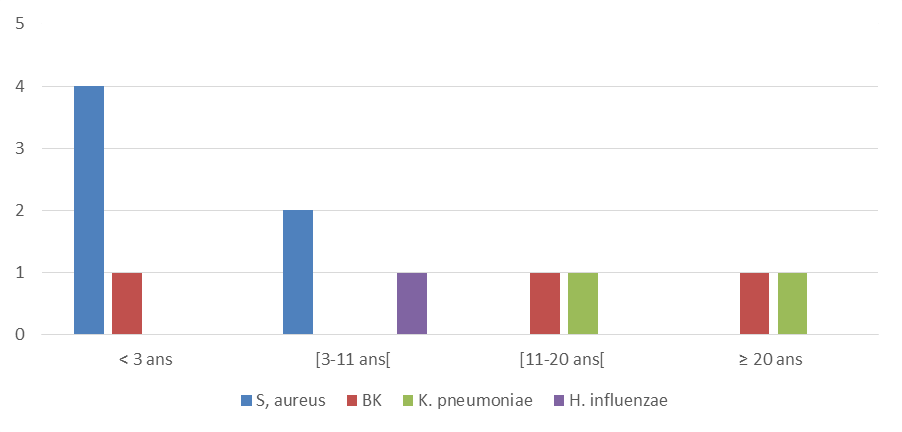

Bacteriology of pleural fluid

Staphylococcus aureus (18.7%) is the first germ the most found in our study. Many studies (Dagnra, A. Y. et al., 2003; Koueta, F. et al., 2011; LUKUNI MASSIKA, L. et al., 1990; Hassan, I., & Mabogunje, O. 1992; & Brémont, F. et al., 1996) [5], [10], [16], [22] & [26] find this germ, followed by pneumococcus. Other series (Yone, E. P. et al., 2012; Garba, M. et al., 2015; Lin, T. Y., et al., 2013; & Hernández‐Bou, S. et al., 2009) [18, 11, 27 & 28] differ in the predominance of the latter. It is also necessary to note the high rate of sterile cultures which was 75%.

Such results in our study can be explained by many intertwined factors:

The effect of pneumococcal vaccination (EPI and national vaccination programs) which produces a natural selection of bacterial ecology and decreases the risk of pneumococcal infection (Koshy, E. et al., 2010; & Schultz, K. D. et al., 2004); [23 & 29]

The use of antibiotics before admission (especially at home), especially beta-lactams, which are generally more active on pneumococcus than staphylococci (secretors of beta-lactamases). This observation influences both our ecology and the crop positivity rate;

The good conditions for collecting and transporting biological fluids to the laboratory, which are not always correct;

The limited resources (insufficiency, lack of appropriate materials) and the difficulty of cultivating anaerobic germs in our context in particular.

In addition, the studies underlined above with a predominance of pneumococcus, all have the first to be prospective, and to have been carried out with a better technical platform (Kit for research of soluble antigens, PCR ...) and a better follow-up. patients. Another peculiarity and observation made in these studies is the presence of at least one immunosuppressive factor (alcohol, tobacco, HIV infection, malnutrition, etc.) in relatively large proportions, favorable to the development of pneumococcus. We must add, despite the vaccination programs established around the world, the possibility of the emergence of pneumococcal serotypes not included in the vaccines used for these studies.

Blood disturbances

Hyperleukocytosis (87.5%), anemia (87.5%) and increased CRP (75%) were the three blood abnormalities found. Many authors (Garba, M. et al., 2015; LUKUNI MASSIKA, L. et al., 1990; Brémont, F. et al., 1996; & Almaramhy, H. H., & Allama, A. M. 2015) [11,16, 27 & 30, ] find the same anomalies, with a few similarities.

Concerning these biological parameters, the literature always reports these same disturbances. In the majority of cases, leukocytes and inflammatory markers (VS or CRP) always come back high, while the Hb level is low. Bacterial etiology, as well as the infectious and inflammatory processes that accompany it, are naturally responsible for these abnormalities.

ETIOLOGY

Purulent pleurisy was post-pneumonic in most (62.5%) of the cases in our series.

This data is consistent with that of ONDO N’DONG et al., (2007), HICHAM et al., (2018), [9 & 25] as well as MALHOTRAA et al., (2007). This global observation is justified by the natural and physiological position of the lungs. These organs are the last place of exchange with the external environment after the passage of air through the upper airways. The contiguity of the lungs with the pleura is the main factor and mechanism of inoculation of bacteria to the pleural space. However, by mechanisms still poorly understood, there are possibilities of direct inoculation, without passage through the lung [1-3].

THERAPEUTIC AND EVOLVING ASPECTS

Medical treatment

All of our patients received antibiotic therapy according to the latest recommendations [1]. It was a beta-lactam (amoxicillin-clavulanic acid or ceftriaxone), sometimes combined with an aminoglycoside. The treatment was then readjusted according to the antibiogram for the cases of positive culture. No case has been completely cured with antibiotic therapy alone, although some authors such as HERNANDEZ-BOU et al., (2018), [28] as well as CARTER et al., (2010) [31] in particular, show that this is possible.

Instrumental treatment

All the patients in this series underwent pleural drainage (31 cases), or iterative puncture (1 case). Thirteen patients (40.6%), including 12 (37.5%) cases of drainage and a single case (3.1%) of iterative punctures, responded favorably, without resorting to surgery.

The results of the literature on the success of first-line drainage are very variable in Africa (Yone, E. P. et al., 2012; Koueta, F. et al., 2011; Garba, M. et al., 2015; & Alao, M. J. et al., 2010) [18, 10, 11 & 32 ] and elsewhere (Kondov, G. et al., 2017; Sakran, W. et al., 2014; & Kumar, A. et al., 2013) [33-35] Many parameters have to be taken into account. First, there is accessibility to the chest tube. From a financial point of view, the drainage kit is not always within the reach of all patients. This naturally results in a delay in laying the drain, which is a limiting factor in the effectiveness of drainage. Another factor that could influence the effectiveness of drainage depending on whether it is long or short is the consultation time. The delay caused by the cost of the drain and the long consultation time have a direct relationship with the pleurisy stage. The longer this delay, the greater the risk of encystment, which is linked to a greater risk of failure. We can easily make this observation in the series of Almaramhy, H. H., & Allama, A. M. (2015) [30], and that of MANDAL et al., (2019) [35]. Another fact that can influence the result of drainage in a population is the tuberculous or non-tuberculous origin of the empyema. KUNDU et al., (2010) [36] show in a prospective study that drainage tends to have better results in pleurisy when the origin is non-tuberculous. Our sample is however too small to make such a comparison.

Surgical treatment

Decortication thoracotomy, indicated as a last resort according to the latest recommendations (Goyal, V. et al., 2014) [24], is the only surgical option in our series. Thoracoscopy, which is the first-line method (Goyal, V. et al., 2014) [24], is not yet available in our department. Eleven patients (34.3%) had undergone decortication thoracotomy, and among them 10 (31.2%) had a favorable outcome. These figures show the failure rate of any other measure of pleural evacuation (drainage and thoracentesis in particular) and the success rate of decortication in this series.

Many series report varying results regarding their surgical method. KUNDU et al., (2010) [36] in their series analyze two types of populations: tuberculous and non-tuberculous etiologies; 55% had required dehulling in the 1st sample, compared to 10.9% in the other. SAKRAN et al., (2014) [34] in their study obtained 64% of their patients who were eligible for surgery (by thoracoscopy in particular). SEMENKOVICH et al., (2018) [37] obtained 44% (including 24% by thoracoscopy and 20% by thoracotomy) in a population that initially benefited from drainage. All these observed disparities largely depend on the success rate of the thoracic drainage. It should be added, however, that the rate of patients who benefit from surgery is influenced by age and clinical status; Young adults cope better with heavy surgeries compared to those at the extreme ages of life. In addition, certain clinical situations with comorbidities do not always bode well for good results.

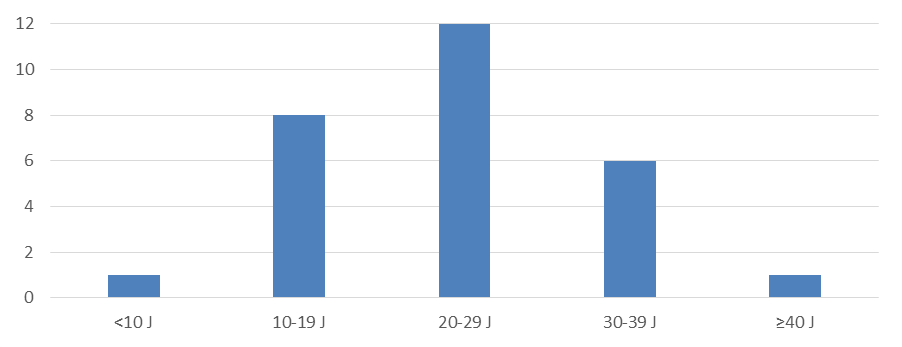

Duration of hospitalization

We obtained a mean hospital stay of 23.7 ± 8.8 J with extremes of 9 and 50 J. A greater proportion (37.2%) of patients was between 20-29 J.

More or less similar results are found. GARBA et al., (1990) [11] found a delay of 22.67 ± 10.97 J. PERFURA et al., (2012) found 26.8 ± 15.6 J. BREMONT et al., (2010) [26] found an average of 24 J with extremes de 15-45 J. In addition, some authors report different results. MEIER et al., (2000) [38] found 14.6 J. MAFFEY et al.,(2019) [39] found an identical mean of 14 ± 6 J. HICHAM et al., (2018) [25] obtained an even lower mean duration of 7 J. This difference in results can be observed justified by many factors. The time taken to take charge is an important element. It is associated with the patient consultation time. These two facts cause a certain delay in the installation of a drain and / or the performance of the surgery, and lengthen the patient's stay. Also, the more invasive the pleural evacuation method, the more it would tend to lengthen the stay. KONDOV et al., (2017) [33] make this observation in a retrospective study: individuals having undergone drainage, decortication or thoracoplasty had respectively 11, 4 J, then 23.3 J and 42.2 J of hospitalization on average. In addition, the existence of comorbidities, the presence of numerous areas of encystment of pleurisy and even the presence of gram-negative bacteria would tend to prolong the stay. GHOSH et al., (2018) [40] make the same observation in a prospective and observational study