Hypertensive diseases in pregnancy comprise chronic hypertension, gestational hypertension and pre-eclampsia. They are a significant cause of morbidity and mortality in the UK and worldwide, with effects on both mother and baby. Pre-eclampsia in particular results in major perinatal and long-term, complications. In the most recent triennial report 2009–2012, [1] it was responsible for the death of 9 women, making it the fourth leading direct cause of maternal death. Many deaths are related to poor management of severe hypertension and eclampsia where the anaesthetist can have a significant role. Fetal implications include increased incidence of placental abruption, preterm delivery and fetal growth restriction where the anaesthetist must provide timely safe anaesthesia to improve outcomes. These risks are not exclusive to pre-eclampsia and it has become clear that pre-existing chronic hypertension is also associated with adverse pregnancy outcomes. This review will describe the pathophysiology, diagnosis, management and recent advances in care of these patients with the primary focus on pre-eclampsia, where the anaesthetist is most involved.

Chronic and Gestational Hypertension

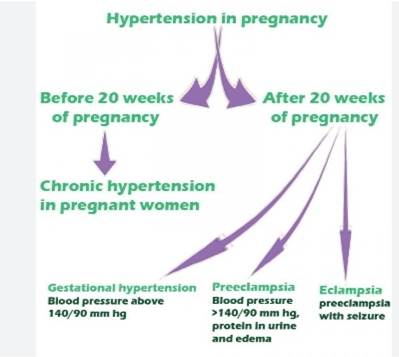

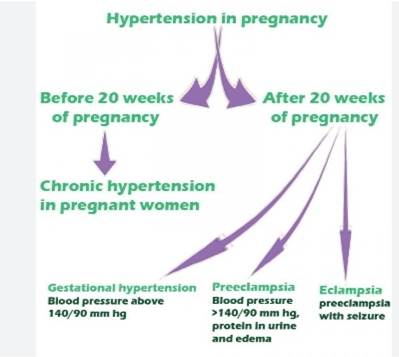

Chronic hypertension is defined as hypertension (systolic blood pressure ≥140mmHg or diastolic blood pressure ≥90mmHg) present at the booking visit or before 20weeks’ gestation, or if the patient is already taking antihypertensive medication. It complicates between 1 and 5% of pregnancies. With advances in fertility techniques, increasing maternal age and increasing obesity, this percentage is expected to increase. Its importance cannot be underestimated with a recent meta-analysis [2] demonstrating increased relative risk for numerous adverse outcomes; superimposed pre-eclampsia, preterm delivery, Caesarean section, low birthweight, admission to neonatal unit and perinatal death. Gestational hypertension is hypertension presenting after 20 weeks’ gestation without significant proteinuria and affects ∼6% of pregnancies. Blood pressure should be controlled to <150/100 mm Hg in both groups (unless there is end-organ damage where target blood pressure is <140/90 mm Hg) and oral labetalol is the first line therapy if the mother can tolerate it. Alternative agents include nifedipine and methyldopa. Women with pre-pregnancy hypertension already taking anti hypertensives should be switched to one of these agents as early as possible, preferably pre-conception, because of their improved safety profile in pregnancy.

Renal function should be regularly monitored with quantification of any proteinuria using spot protein: creatinine ratio. Delivery is not usually indicated until 37 weeks’ gestation provided blood pressure is <160/110 mm Hg, the fetus is growing well and the mother does not get superimposed pre-eclampsia. Timing of delivery often requires multidisciplinary discussions between obstetricians, anaesthetists and neonatologists to optimize fetal maturity whilst taking into account fetal growth and maternal morbidity, such as renal dysfunction [3].

Pre-Eclampsia

Definition and Diagnosis

Pre-eclampsia is defined as hypertension presenting after 20 weeks’ gestation with significant proteinuria (spot urinary protein: Creatinine ratio >30 mg mmol−1 or a 24-h urine collection with >300 mg protein) [3]. Proteinuria signifies endothelial damage characteristic of pre-eclampsia. The dependence of normal kidney function on adequate blood flow and selective glomerular filtration makes it vulnerable to these endothelial changes. Preeclampsia can be superimposed on women who have hypertension or proteinuria before 20 weeks’ gestation and diagnosis can be more problematic in these patients. Worsening disease may be indicated by a sudden increase in blood pressure, new onset or worsening proteinuria, or evidence of involvement of other organ systems such as elevated liver enzymes or thrombocytopenia [4]. Pre-eclampsia is classified as severe when there is proteinuria with severe hypertension (≥160/100 mm Hg) or mild to moderate hypertension (140/90–159/109 mm Hg).

Risk Factors

Numerous risk factors for the development of pre-eclampsia have been identified including nulliparity, previous pre-eclampsia, multiple pregnancy, maternal age >40 yr, BMI ≥35 kgm−2 before pregnancy, family history of pre-eclampsia, pre-existing diabetes, hypertension, renal disease, antiphospholipid syndrome and an inter-pregnancy gap of >10 year [5]. A genetic contribution has been hypothesized but there is, as yet, no evidence to support the role of any particular gene [4].

Pathogenesis

Several pathogenic mechanisms for pre-eclampsia have been proposed. It is generally accepted that impaired trophoblastic cell invasion results in failure of spiral artery dilatation, leading to placental hypoperfusion and consequently hypoxia. In response to hypoxia, the placenta releases cytokines and inflammatory factors into the maternal circulation triggering endothelial dysfunction. The subsequent increase in vascular reactivity and permeability and coagulation cascade activation, results in organ dysfunction [4].

Prevention

The significant morbidity caused by pre-eclampsia has led to considerable interest in preventative measures. Progress has been hindered by an incomplete understanding of pathogenesis, but some evidence exists in favour of a number of interventions.

Aspirin

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence recommends 75 mg aspirin daily from 12 weeks’ gestation until 36–37 weeks’ gestation for any woman with one high, or two or more moderate, risk factors. This is based on the results of a meta-analysis showing a 50% relative risk reduction for the development of pre-eclampsia in high-risk women (identified by abnormal uterine artery Doppler in the first trimester of pregnancy) who started taking aspirin before 16 weeks’ gestation [6]. The proposed mechanism of action is a reduction in platelet production of thromboxane relative to prostacyclin and hence reduced vasoconstriction.

Calcium

In populations with low dietary calcium, calcium supplementation can reduce the incidence of pre-eclampsia. Owing to the rarity of calcium deficiency in the developed world, calcium supplementation is not currently recommended in the UK despite the low risk of harm.

Bariatric Surgery

Obesity is strongly associated with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and there is evidence that bariatric surgery decreases the incidence of hypertension in pregnancy in obese women by ∼75% [7]. It is uncertain whether weight loss by other methods can confer similar risk reductions.

Folic Acid

The ongoing Folic Acid Clinical Trial (FACT) is a phase III, doubleblinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial assessing the effect of high-dose folic acid (4 mg day−1) on the incidence of pre-eclampsia in women deemed high risk. It is based on several cohort studies that have suggested a protective effect. Recruitment is attributable to finish in 2015 (Figure 1).

Management

Blood Pressure:The principal aim of blood pressure control in pre-eclampsia is the prevention of intracerebral haemorrhage. It is recommended to aim for systolic and diastolic blood pressures of <150 and 80–100 mm Hg, respectively, although rapid reductions in blood pressure may result in complications to both mother and fetus.

Figure 1: Classification of Hypertension in Pregnancy

The rate of reduction should be ∼1–2 mm Hg every minute. Oral labetalol is often first choice, but alternatives include nifedipine and methyldopa. Nifedipine should be used cautiously with magnesium sulphate as a result of the possible toxic effects of a calcium-channel blocker with magnesium therapy. In cases of severe hypertension, oral therapy may be inadequate and more reliable control achieved with i.v. labetalol or hydralazine. Hydralazine can cause maternal tachycardia and sudden hypotension and it may be necessary to cautiously preload women with 500 mL crystalloid solution. Once the mother requires i.v. antihypertensive therapy with fluid restriction, the option of invasive blood pressure monitoring in a high dependency area should be considered and also regular urine output monitoring and 6-hourly blood tests to monitor platelet count, renal function and liver enzymes. Continuous fetal monitoring should be carried out until blood pressure is stable.

Seizures

Eclamptic seizures are a significant cause of mortality in preeclampsia and are associated with intracerebral haemorrhage and cardiac arrest. Magnesium sulphate is first-line therapy for treatment and prevention of eclamptic seizures and has been shown to reduce the incidence of seizures in patients with severe pre-eclampsia by >50%. The Collaborative Eclampsia Trial recommended a loading dose of 4–5 g over 5 min followed by an infusion of 1 g h−1 for 24 h through a volumetric infusion pump.

Recurrent seizures are treated with further 2 g boluses. Despite some antihypertensive effects, magnesium sulphate does not normally adequately lower blood pressure in pre-eclampsia and is therefore not recommended as the sole antihypertensive agent, although the additive effect of repeated bolus doses of magnesium sulphate with recurrent seizures can cause significant hypotension. Where preterm delivery within the next 24 h is anticipated, magnesium sulphate provides the additional benefit of rapid fetal neuroprotection and reduced risk of cerebral palsy [8]. Patients receiving magnesium sulphate should be regularly monitored for evidence of toxicity, as indicated by diminished reflexes, low respiratory rate or low oxygen saturations and progressive paralysis. Renal impairment with low urine output may predispose to magnesium toxicity and if suspected administration should cease and serum magnesium levels be checked. The treatment for magnesium toxicity is calcium gluconate (10 mL of 10% solution over 10 min). Magnesium sulphate causes a reduction in the normal sympathetic tone of the fetus, reducing variability in the cardiotocograph and making interpretation difficult for the obstetrician.

Pulmonary Oedema

Acute pulmonary oedema occurs in up to 3% of cases of preeclampsia with the potential to cause maternal mortality. The majority of cases (∼70%) occur after delivery and are often associated with heart failure and excess fluid administration. Consequently, fluid restriction to 80 mL h−1 (oral, drugs and i.v. fluid combined) is recommended for women with severe pre-eclampsia, provided there are no ongoing fluid losses [3]. Diagnosis is based on clinical findings, chest radiograph (even if the mother is still pregnant) and in severe cases an urgent echocardiogram to assess ventricular function. First-line treatment is with oxygen, fluid restriction, furosemide boluses of 20–60 mg and urgent delivery of the fetus. Sufficient oxygen delivery may require noninvasive or invasive ventilatory support. The role of morphine (in boluses of 2–5 mg) is now more controversial, with the potential benefits of mild systemic venodilatation, reduced anxiety and dyspnoea potentially outweighed by reduced ventilatory drive. In severe cases, usually associated with renal impairment, the response to furosemide may be inadequate. In these rare circumstances, glyceryl trinitrate may be required [9,10] and should be given as an infusion starting at 5 μg min−1 increased as necessary every 3 to 5 min to a maximum of 100 μg min−1.

Analgesia

The majority of women with severe pre-eclampsia will benefit from neuraxial analgesia in labour, through prevention of the hypertensive response to pain and the resulting sympathetic block contributing to the overall anti-hypertensive strategy. In addition, an indwelling epidural catheter enables the provision of surgical anaesthesia should operative delivery become necessary.

The contraindications specific to pre-eclampsia are thrombocytopenia, rapidly decreasing platelets, or more rarely disseminated intravascular coagulation. For this reason full blood count and coagulation studies are required within 6 h in all cases and 2 h in severe cases, before performing central neuraxial blockade. It has been suggested that central neuraxial blockade should not be performed below a platelet count of 75– 100×10−9 litre−1 with extra care required for rapidly decreasing counts. Pre-loading with fluid is not usually required for preeclamptic patients receiving low-dose central neuraxial analgesia but careful blood-pressure monitoring with small doses of a vasopressor may be necessary, as sudden decreases in blood pressure can be poorly tolerated by the fetus. When central neuraxial blockade is contraindicated, i.v. opioids provide an appropriate alternative, with remifentanil patient controlled analgesia gaining popularity. Postpartum analgesia will vary depending on mode of delivery but may include intrathecal or i.v. opioids, abdominal wall nerve blocks or wound infiltration and simple analgesics such as paracetamol. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should be avoided until a postpartum dieresis with normal renal function is confirmed.

Anaesthesia

Central neuraxial blockade is the anaesthetic technique of choice for the majority of pre-eclamptic women requiring operative delivery. Spinal, epidural and combined spinal-epidural are all used successfully with no evidence in favour of one particular technique. Hypotension secondary to regional anaesthesia, although less common than in non pre-eclamptic patients, can still occur and should be managed with boluses of phenylephrine or ephedrine, titrated to effect. Alternatively, phenylephrine infusions may be used, provided adequate care is taken due to the increased sensitivity to these drugs. Invasive blood pressure monitoring is useful especially if the mother is already requiring magnesium sulphate and i.v. anti-hypertensives. General anaesthesia may be necessary if regional techniques are contraindicated due to clotting abnormalities. The hypertensive response to laryngoscopy must be actively managed as this has been directly linked with maternal deaths. This can be achieved with a number of pharmacological agents including alfentanil, remifentanil, lidocaine, esmolol, labetalol, magnesium sulphate and a combination of the aforementioned. No drug has been shown to be superior and so the anaesthetist should choose that with which they are most familiar. Hypertension on emergence from anaesthesia is also common and repeat boluses of the above drugs may be necessary. The upper airway oedema of the preeclamptic patient may necessitate a smaller than predicted tracheal tube diameter and care on extubation is also required. The action of succinylcholine is unaffected by magnesium sulphate although the appearance of the characteristic fasciculations may be reduced. All the non-depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agents are potentiated by magnesium sulphate and a smaller dose than usual may be required with careful monitoring of adequate reversal into the postoperative period.

Postpartum haemorrhage Pre-eclampsia is a recognized risk factor for Postpartum Haemorrhage (PPH) possibly due to the associated thrombocytopenia, liver disease with reduced clotting factor production, DIC and the restricted use of uterotonics. Syntocinon 5 units given as a slow i.v. or i.m. injection is first-line pharmacological treatment which can be repeated if necessary and continued as an infusion of 10 units h−1. Care should be taken not to exceed fluid restrictions and preparation in smaller than usual volumes may be required. Ergometrine is generally contraindicated due to its liability to increase blood pressure and so second-line treatment is with carboprost 250 μg intramuscularly or misoprostol 1000 μg rectally [11]. Only in extreme unresponsive atonic haemorrhage with delayed access to surgery, should ergometrine be considered. If required it should be given either intramuscularly in divided doses or very small i.v. doses after dilution. There is a significant risk of pulmonary oedema when managing a preeclamptic patient with postpartum haemorrhage and monitoring central venous pressures may be helpful. Continuous oxygen saturation monitoring for the first 24 h post-delivery is sensitive to developing pulmonary problems.

Recent Advances

Echocardiography: As a consequence of the considerable cardiopulmonary morbidity and mortality in pre-eclampsia, a significant amount of recent research has focused on ways to optimize this aspect of management.

Echocardiography is emerging as an extremely useful tool investigation, with recent studies shedding new light on the cardiovascular changes in pre-eclampsia. It has been demonstrated that patients with severe pre-eclampsia have increased cardiac output, increased contractility and mild vasoconstriction, all of which contribute to hypertension. The increase in cardiac output results from an increased stroke volume as a consequence of increased contractility, rather than increased left ventricular end-diastolic volume. In addition, it has been shown that there is diastolic dysfunction due to a combination of increased left ventricular mass and pericardial effusions, hence the predisposition to pulmonary oedema [12]. Echocardiography can also be used to aid management of women with pre-eclampsia by enabling more informed decisions regarding need for fluid therapy and choice of antihypertensive agen [13]. It may also be possible to use echocardiography as an additional intra-operative and postoperative monitoring tool. Echocardiography is now a relatively routine investigation in the non-pregnant hypertensive patient as it provides a robust evaluation of cardiac function. It seems likely that its use in the hypertensive pregnant patient will become more widespread in the near future.

Placental Growth Factor

The diagnosis of pre-eclampsia is currently based on the presence of hypertension and proteinuria indicating organ dysfunction. There has been considerable effort to identify other markers that may aid in an earlier diagnosis to enable closer monitoring of the mother and fetus with the potential to improve outcomes. Placental Growth Factor (PlGF) is an angiogenic factor produced by the placenta, with peak concentrations occurring between 26 and 30 weeks’ gestation. Maternal levels of PlGF have been shown to be reduced in women with pre-eclampsia, with the lowest levels corresponding to earlier onset and increased disease severity. A recent study which recruited women with suspected pre-eclampsia (but without the diagnostic combination of hypertension and proteinuria), from 20weeks’gestation onwards, demonstrated that low levels of PlGF (<100 pg mL−1) are highly sensitive in predicting the need for delivery due to pre-eclampsia within 14 days. The importance of this novel biomarker lies in its ability to diagnose pre-eclampsia before the onset of hypertension and proteinuria, thus allowing earlier treatment and multidisciplinary planning for delivery. Levels of PlGF naturally decline during the third trimester and so the test becomes less reliable after 35 weeks [14] Randomized controlled trials are required to assess whether diagnosing preeclampsia with PlGF rather than current methods can improve maternal and/or fetal outcomes.