Dracunculiasis has been considered as one of the most neglected tropical diseases (NTD) as first parasitic infection targeted for eradication globally. This is caused by a Guinea worm, Dracunculus medinensis (Figure 1) developing the “Guinea worm Disease” (GWD) in human. This is a kind of extremely rare and neglected tropical disease with rarely fatal consequences but developing serious complications and lifelong permanent disabilities in human [1], [2] D. medinensis is a parasitic nematode worm (60-100cm long) exclusively transmitted in human via contaminated drinking water with infected water fleas. In fact, these water fleas (Crustacean copepods, cyclops) (Figure 2) feed on Guinea worms. Sometimes, the infection also took place when undercooked aquatic foods and fishes are consumed [3]. The disease is known to us since antiquity and the worm has been around us far thousands of years. This is endemic in regions with poverty in some African countries live Ethiopia, Chad, Mali and South Sudan. The infection mostly occurs in areas where the drinking water is not safe and contaminated with the water fleas and Guinea worms [4].

Figure 1. Dracunculus medinensis or Guinea worm

(Photo Credited from Katernakon, deposit photos,

Image ID 370931154)

Figure 2. A Cyclop (Photo Credited from Dreamstime,Stock photos, ID 36293222)

Figure 2. A Cyclop (Photo Credited from Dreamstime,Stock photos, ID 36293222)

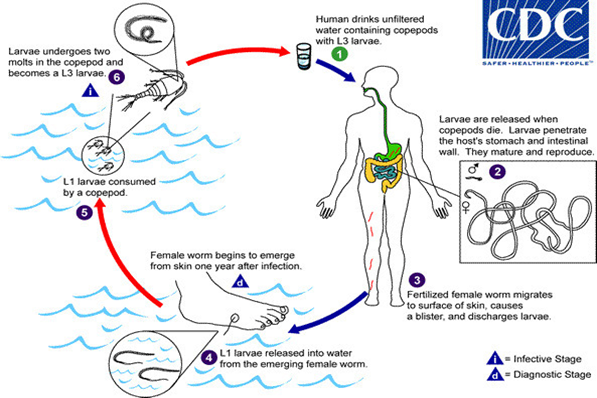

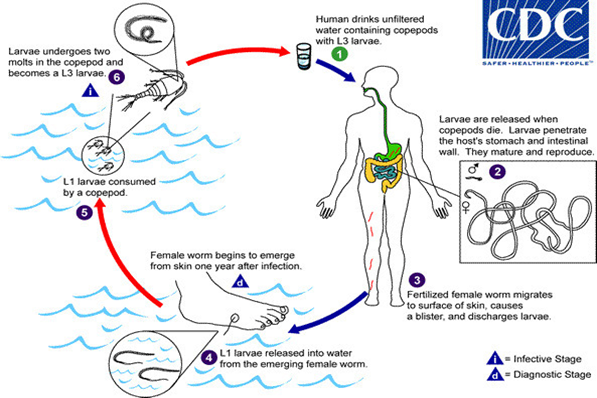

The copepods ingested with the drinking water died upon leaving the larvae inside the human stomach. After mating male dies and transformed larvae in adults in about-2 weeks, are moved via piercing stomach and intestinal walls eventually reaching the underlayer of skin in a year developed blisters mostly on legs and feet. In due course, the eruption took place releasing the larvae from the skin. The females also die during the process and it not.

Figure 3. Life Cycle of Dracunculiasis (Credited and Contributed from CDC)

Figure 3. Life Cycle of Dracunculiasis (Credited andContributed from CDC)

Figure 4. Guinea worm extraction from leg

(Photo Credit: 2001, The Carter Centre)

Removed within time, they are calcified and encapsulate developing sepsis and extremely painful arthritis and contractures. The ingestion of contaminated drinking water with cyclops containing larvae by humans started the disease cycle again [5], [6], [7] (Figure 3). The disease is easily diagnosed by observing the worms releasing from the erupted blisters in water. The disease symptoms only appear after a year when the eruption took place. However, the entire process of the development of blisters and eruption has been very painful with intense itching and burning (Figure 4). A patient suffering from the same disease may only get some relief by immersing the affected part in water. The associated clinical symptoms of the disease are fever, nausea and vomiting, diarrhoea, peripheral eosinophilia and feeling unwell. The disease complications may occur when the worms are migrated to other body parts like lungs, pericardium of spinal cord [7], [5]. There are no effective medications and vaccines are available and only symptomatic relieves be given to the patient. The first choice of drugs for physicians are ibuprofen and aspirin for the relief of pain and swelling. Similarly, diphenylhydramine is prescribed for itching. To prevent the secondary bacterial wound infections, the antibiotics are prescribed. Topical antibiotic ointments and creams are also suggested. However, prognosis of the disease is very poor. Further, to prevent the disease, the removal of worms either surgically or physically in water are utmost needed. More than 90% worms are released with the use of sticks for winding from legs and feet (Figure 5). This is a very tedious job as the worm can be pulled out only a few centimetres each day. It may take even weeks to complete the process. The calcified dead worms can also easily be visualized by the X rays and are surgically removal [7], [8], [9]. Quite a large number of humans were affected with the disease in Middle East, Africa and India. But following the Guinea Worm Eradication Programs initiated by WHO, the number of cases has reduced significantly. According to an estimate, the cases have decreased from 3.5 million in 1986 to 27 in 2020 with only six countries affected. They are Ethiopia, Angola, Chad, Mali, Cameroon and South Sudan. This is almost absolute achievement of eradication of Guinea worm disease globally.

Figure 5. A method used to extract a Guinea worm

Figure 5. A method used to extract a Guinea worm

(Photo Credited from CDC, PHIL, ID No#1342)

Figure 2. A Cyclop (Photo Credited from Dreamstime,Stock photos, ID 36293222)

Figure 2. A Cyclop (Photo Credited from Dreamstime,Stock photos, ID 36293222)

Figure 5. A method used to extract a Guinea worm

Figure 5. A method used to extract a Guinea worm